Father, brother: Norman Fischer’s path to the priesthood nurtured by Centre community

When Norman Fischer came to Centre College, he realized his career goals might be different than many of his classmates.

While they planned to become doctors, lawyers, executives and artists, he was considering the Roman Catholic priesthood. Father Bill Spalding, his first mentor, had predicted that would be the case when Fischer was a 10-year-old altar boy at Saint Mary’s Catholic Church in Perryville, Kentucky.

“So I pretty much kept my nose clean,” said Fischer, who graduated in 1995 with a double major in art and psychology. “I felt, what if I’m a priest? I had better start practicing what this will be like. So I tried to live as Christ calls us to live, and everything else is just grace.”

Fischer, 49, was born at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. His older brother and sister were born at Clark Air Base in the Philippines, where his father, Norman Fischer Sr., met and married their Filipino mother, Lecita. After the Air Force, the devout Catholic family moved back to a family farm in Boyle County.

“I was a farm boy,” Fischer said. “I grew up raising tobacco and cattle, learning the importance of hard work and the fruit of your labors.”

Fischer said his Centre experience helped give him the confidence and wisdom he would later rely on as the Lexington Diocese’s first Black priest.

After earning a Master of Divinity degree at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake in Illinois, Fischer was ordained and served short stints at churches in Winchester and Mt. Sterling.

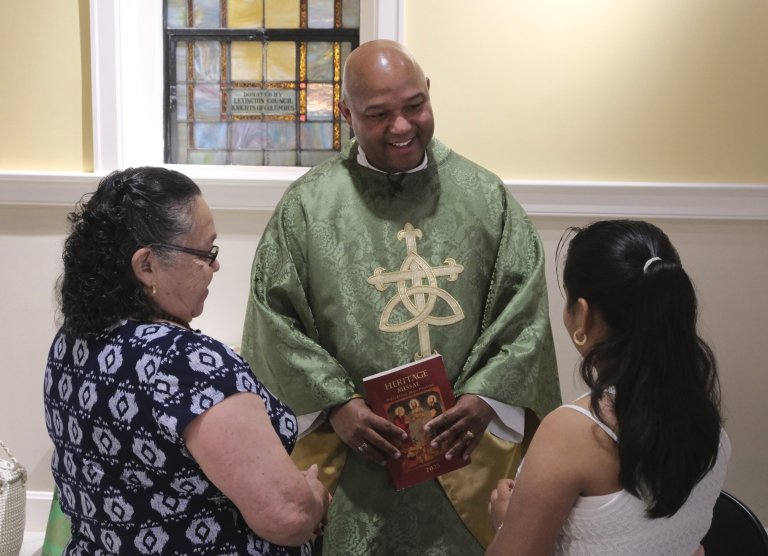

For the past 17 years, he has been chaplain at Lexington Catholic High School and pastor of historic Saint Peter Claver Catholic Church in Lexington’s northside neighborhood, where he led the recent completion of a $6 million facility renovation and expansion. Fischer’s imprint can be seen around the new sanctuary.

“He’s an artist at heart, so many of the visual things here are his inspiration,” said Deacon James Weathers, the parish life director. “It’s been a godsend.”

Fischer’s art education at Centre influenced his choices of paintings and decoration in St. Peter Claver’s sanctuary, which celebrate Black saints and African iconography. A painting of a Black St. Michael the Archangel trampling Satan was done by Lexington Catholic graduate Amber Pitts Knorr, who is now studying sacred art in Italy.

“We wanted to have art that spoke to the African American experience and the African experience, which is oftentimes not a story you find in Catholic churches,” Fischer said.

The church is named for a Spanish Jesuit priest who, in early 1600s Colombia, became known as the patron saint of slaves. St. Peter Claver is the most diverse church in the diocese. Fischer estimates that of nearly 300 parish families, half are African American and the other half is a mixture of white, African, Latino and other ethnicities. At a recent weekday mass, Fischer made the key points of his homily in Spanish as well as English.

“Martin Luther King Jr. said Sunday was the most segregated day of the week,” he said. “But for us, that’s not true.”

As chaplain at Lexington Catholic, Fischer does some teaching, but is mostly there to support the faculty, staff and students.

“Unfortunately, I've done so many parents' funerals, so many suicides, so many drug overdoses; I've experienced the tragedy and fragility of students through car accidents,” he said. “You've really got to stretch your heart for the needs of the teens.”

Fischer isn’t just there for the students during the hard times. He also cheers them on at school functions and sporting events, chatting with them in the hallway between classes.

“It’s fun,” he said. “They love when you come around and when you're invested in their story and their journey.”

Both his church and school roles are about building community — something he said he learned to appreciate at Centre, where faith traditions are respected.

“As a Catholic, I was able to be a part of different organizations and even create some ministries on campus,” he said. “I was blessed to have prayer groups in the basement of the freshman dorm.” He served two years as a residence hall RA and was chaplain of Sigma Chi fraternity. Off campus, he taught seventh graders and sang at Saints Peter and Paul Catholic Church.

“They had a program called Centre Action Reaches Everyone (CARE), which is how I ended up getting a chance to volunteer and do service” as a big brother for two children in foster care, he said. Fischer competed in track and field and was active in the Black Student Union.

Fischer’s fraternity brothers now refer to him as “Father Brother,” said Brook Forrest White Jr., a fellow Sigma Chi and art graduate who now runs the Flame Run glass studio in Louisville.

“Norman was an exceptionally talented artist, but he was good at many different things,” said White, who noted that he believed the Centre experience helped Fischer relate to a wide range of people. “Norman has been a positive influence on my life and many others. He’s done a lot of good.”

The new blown glass holy water font at St. Peter Claver was made by the late Centre art professor Stephen Rolfe Powell ’74 and given by his widow, Shelly. Fischer studied with Powell, who became his mentor at Centre. “I was influenced by his colors, by his vision, his creativity,” Fischer said. Travis Adams ’14 used Powell’s murrini — the colorful bits of glass the world-renowned artist used to make his distinctive sculptures — to make stoppers for the bottles that hold the church’s holy oils.

Fischer said Centre’s small student-faculty ratio allowed him to form lasting bonds with professors such as Powell and Phyllis Passariello, an anthropology professor “who brought the world to us through her experiences.”

“You realize it's a small community, but it has a lot of opportunity,” he said. “We might be small, but we can do mighty things. I felt like I wasn't just learning for the class's sake; I was learning for the world's sake.”